No community mental health awareness is easy. There are always a few pre-requisites of engagement, key messages and delivery approaches to get those messages through. But the majority of models do not go beyond the paprticipant group, thus are not sustainable.

Hence, the Train-of-Trainer (cascade) framework adopted in this project in disadvantaged Karachi communities, of which awareness was only ther first step. It is harder, as one has to work at multiple levels in training and supporting trainers to work with communities, but it is so much more rewarding.

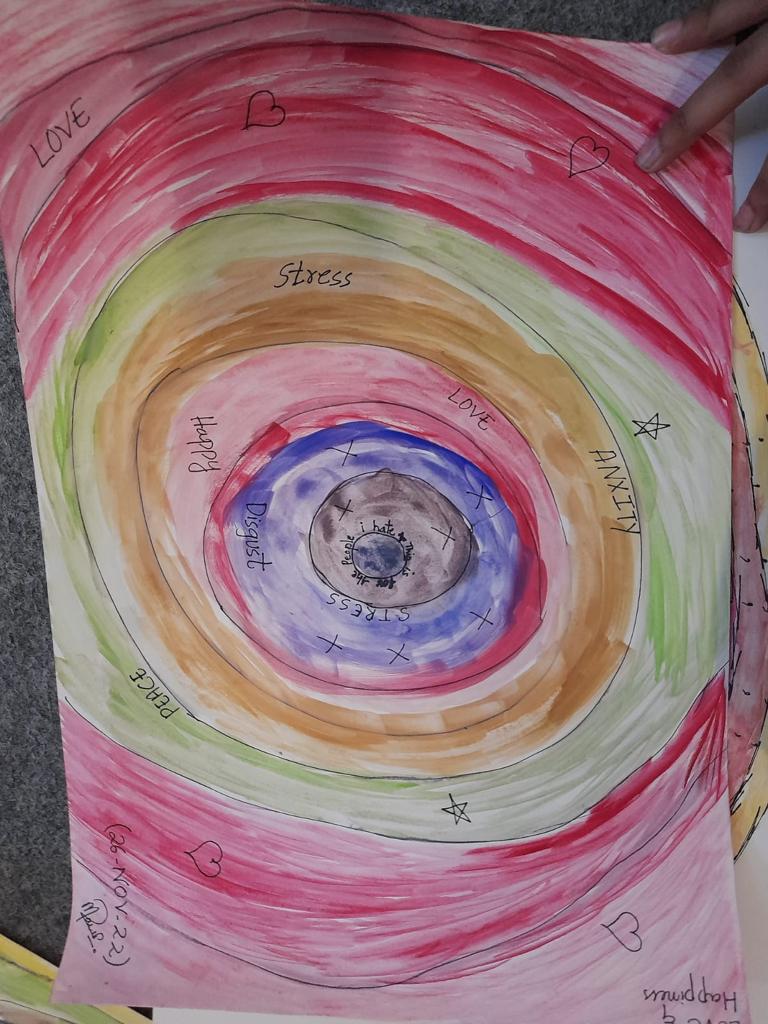

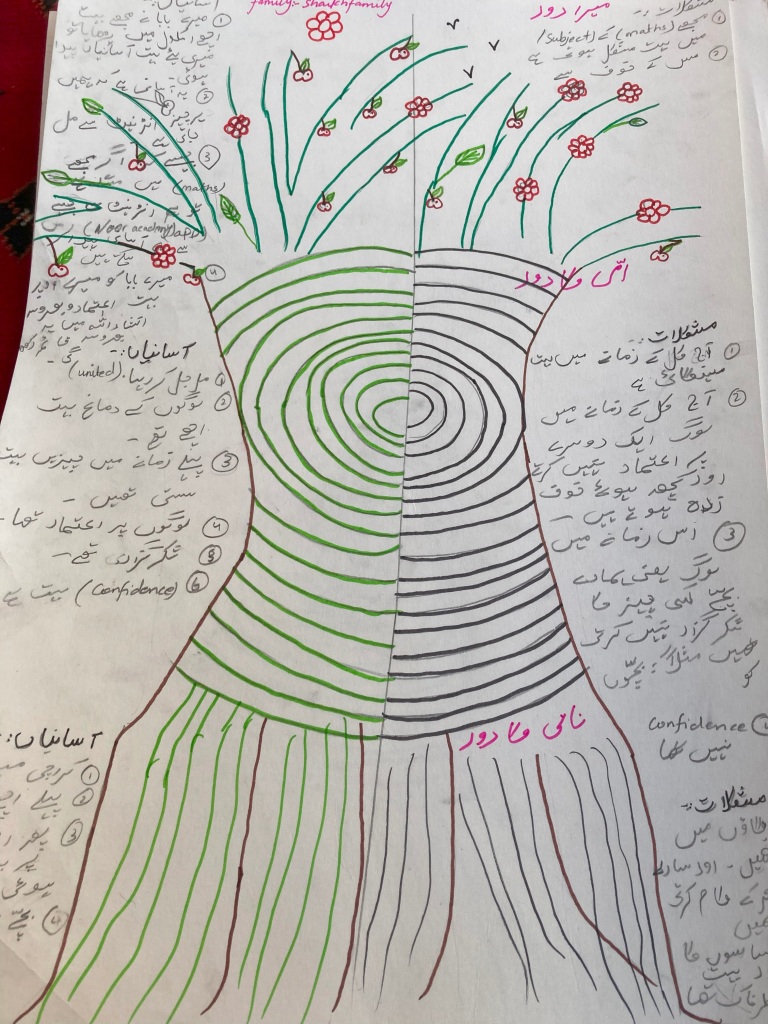

Why? Because trainers come from the same communities, therefore hold unique expertise and credibility. Because they utilize their position to co-produce new knolwedge and mobilize communities that would find external professionals more distanced. Because community participants (in this case youth and parents) can model themseleves on the trainers and feel empowered to cascade this new knowledge within their family (including extended unit), peer group, school and neighbourhood. All these components will ultimately improve help-seeking and lead to better psychosocial integration of existing services. The link of the new paper:

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mhp.2024.200339